I’m reading a book right now called “Hearin the Changes”, by Coker, Knapp, and Vincent. The book’s preface talks about how we create lots of memories of sounds at a subliminal level, but recall or recognition of unconsciously recorded memories can be difficult, they compare it to recognizing a person’s face but not being able to place where you’ve seen them before. This book uses numerical analysis to describe common harmonic pathways in jazz, and points to specific measures in songs where you can hear them, and consciously tag them so you can recognize the harmonic changes when you hear them elsewhere in the future. So the book is promoting active listening to train your ear to recognize changes and identify them in the future in unknown songs. It is a little advanced for me, (IFR’s Pure Harmony Essentials is probably the best fit for me to work on improvising), but a fun way to challenge myself and keep an eye on my goal of becoming musically conversant and able to orient myself in the music I love.

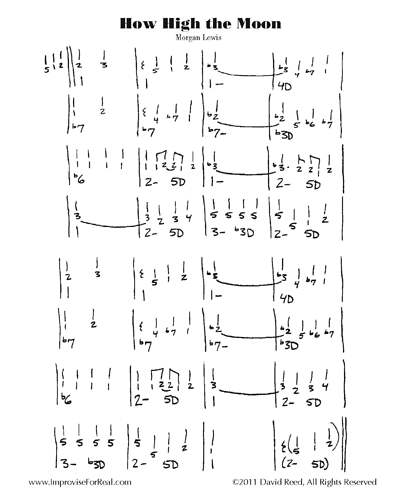

Some of the examples in this book bring up questions in my mind relating to IFR’s tonal approach to ear training, specifically when/how one deals with key changes. One of the harmonic pathways described in the book is called a downstep modulation, tonicizing a whole step down, usually in a series of steps. A good example is “How High the Moon”: 1, 1- (2 of b7), 4D (5D of b7), b7, b7- (2 of b6), b3D (5D of b6), b6. Then it does a 2-b5, 5D, 1-, 2-b5, 5D, 1. So it spends the first two measures in G, the next 10 measures exploring what might be perceived as the keys of F, Eb, and G minor, then back to G major for 6 measures with a lovely 2-, 5D, 3-, b3D (tritone sub for 5D of 2), 2-, 5D, 1, and then we are back into the downstep modulation through b7 to b6, and back to 1. This book “Hearin the Changes” is careful to point out that many temporary distortions of the harmonic environment are not really key changes, but it considers these downstep modulations to be an example of genuine key changes. I’ve also seen “How High the Moon” interpreted elsewhere as I described above using IFR’s naming scheme, so temporary distortions of the original key. I’m curious, those of you with more developed ears than me, do you hear the downstep modulations in “How High the Moon” as a temporary departure from and return to the original key, or a progressive distortion and resolution of the original key? I know the answer to questions like these are often “what matters is how it sounds to the listener”, but I’m still early in my development and learning to identify the square pegs and round holes.

Does anyone have other suggestions for active listening exercises with jazz standards?